Rebecca Newton

28.02.2026

“Hormone balance” is everywhere right now, and it’s sold as the answer to everything from fatigue and breakouts to bloating and bad moods. The problem with how the concept is being sold is that it implies there’s an ideal, static state your body should sit in, and that any symptoms we’re experiencing mean we’ve fallen out of it. But hormones don’t work like a thermostat we can set and forget. They’re dynamic chemical messengers our body uses to coordinate energy, reproduction, stress response, appetite, sleep, and recovery – and they adjust in real time to what we're doing in our lives.

Hormones are the output of interconnected systems.

The HPA axis (hypothalamus- pituitary- adrenal) regulates stress signaling and cortisol rhythm.

The HPG axis (hypothalamus- pituitary- gonadal) coordinates ovulation and sex hormone production.

The HPT axis (hypothalamus- pituitary- thyroid) regulates metabolic rate and how we use energy.

On top of that, hormones are shaped by feedback loops from the nervous system, the immune system, the gut, and peripheral tissues like adipose (fat) and muscle. The point of the systems isn't a single balanced number; instead, they adapt and adjust based on our biological state. A great example is what happens when we’re sleep deprived. After several nights of poor sleep and high stress, there’s a metabolic cascade that impacts everything from focus and mood to metabolism and menstrual health. In this state, the primary stress hormone, cortisol, stays elevated for longer and falls out of its usual diurnal rhythm. Appetite hormones will also change, which results in stronger cravings. And finally, insulin sensitivity decreases, making us less able to control our blood sugar and energy availability.

Depending on the severity and duration of the issues, our sex hormones can then also adapt by deprioritizing ovulation - even if we haven’t changed what we’re eating or our exercise regime. This isn’t a ‘hormone imbalance’ per se - it’s a hormonal adaptation that happens because of a high stress environment.

Most hormones operate across a fairly broad reference range. In blood tests, “normal” is based on a spectrum, and for many hormones- especially sex hormones- levels change meaningfully across both the day and the month. If the system around the hormones - glucose stability, stress, sleep, inflammation, and fuel availability - is unstable, we can still experience a whole host of symptoms despite our hormones being within ‘normal’ range.

REFRAMING HOW WE VIEW HORMONES

A more accurate way to think about hormones is as a part of a feedback network that is continually adapting based on the signals it’s getting from inputs. These include:

Energy availability: are you adequately fuelled, under-eating?

Glucose regulation: is blood sugar stable, or swinging between spikes and crashes?

Stress: is your nervous system constantly switched on?

Nutrient status: are the biochemical pathways resourced?),

Gut resilience: are you fuelling your microbiome with enough fibre and plant diversity to support digestion, absorption, and hormone detoxification?

HORMONES SHIFTS EXPOSE IMBALANCE

The interaction between these factors also helps explain why natural hormone shifts can expose issues in our lifestyle. Across the menstrual cycle, changes in estrogen and progesterone alter insulin sensitivity, fluid balance, how well we sleep, and stress reactivity. When our baseline physiology is robust, we may barely notice this change. When our system is taxed – whether it be low fuel, unstable blood sugar, high stress load, or poor sleep, these normal shifts reduce our biological bandwidth and symptoms will become more prominent.

Perimenopause works similarly but over a longer timeline. Fluctuating hormones do result in symptoms, but they also reduce our tolerance to stressors or lifestyle habits we could previously absorb.

This is why balancing hormones as the starting point often doesn’t work or can feel like a lifelong pursuit. It targets the signal (estrogen, progesterone) rather than the upstream regulators that influence them. Our endocrine output is governed by feedback loops across energy availability, glycaemic variability and insulin demand, and stress signalling via the HPA axis, so when those inputs are unstable, hormonal patterns shift as an adaptive response. Crucially, these adaptations often occur within broad reference ranges on labs because normal is a spectrum, and hormones fluctuate by design. Perimenopause makes the balance framing even less accurate. Ovarian hormone production during this phase will slowly decline over time until it reaches its new baseline; we can’t “balance” our way back to previous levels without using HRT.

WHAT TO FOCUS ON INSTEAD

The good news is that when we address the inputs that help control our hormones, we can drastically improve how we experience them. Over the next month, we'll dive into how blood sugar, stress physiology, and fuel availability impact hormones, and what you can do about to to feel and function better everyday. Next week, we'll be discussing how blood sugar impacts hormones.

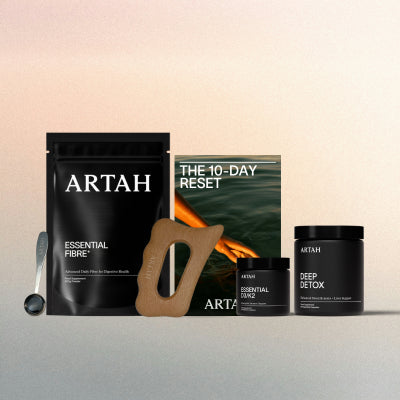

EXPLORE THE COLELCTION

Disclaimer: The information presented in this article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, prevent, or treat any medical or psychological conditions. The information is not intended as medical advice, nor should it replace the advice from a doctor or qualified healthcare professional. Please do not stop, adjust, or modify your dose of any prescribed medications without the direct supervision of your healthcare practitioner.

Read More